Behind the Buy: Why It’s Hard to Change & Adopt New Tech (and What Helps Your Audience Do It)

Picture it.

A longtime subscriber who doesn’t quite feel comfortable with mobile tickets rushes into the theatre just before curtain, flustered from traffic. Their phone won’t load their tickets, the screen won’t brighten, and they feel embarrassed fumbling in front of their guest. The next day they call to let you know they’re never using mobile tickets again.

People don’t like to change because they’re protecting their time, energy, and image.

That’s especially true when we ask our audience members to adopt new technology. And at the pace tech is going these days, even my Gen Z cousin says it’s too much, too fast.

This post breaks down why change feels hard and how we can make it easier on our audiences.

Let’s get into it.

Why People Don’t Like to Change

“What looks like resistance is often a lack of clarity.”

“What looks like laziness is often exhaustion.”

“What looks like a people problem is often a situation problem.”

— Chip Heath, Switch: How to Change Things When Change Is Hard

#1 Habits & Familiarity = Less Mental Energy

Our brains constantly look for shortcuts. Habits let us function on autopilot, saving mental energy for everything else.

Psychologists Wendy Wood, Jeffrey Quinn, and Deborah Kashy (2002) found that habits reduce cognitive load by shifting control from the decision-making part of the brain (the prefrontal cortex) to the automatic-processing center (the basal ganglia).

That’s why even when there’s a better option — like pre-ordering drinks so they’re ready at intermission — the brain sticks with what it already knows. It’s faster, safer, and predictable — standing in a long line, handing over a credit card, and waiting for your drink.

When people say, “I’ll just print my ticket,” they’re saving brainpower for everything else going on that day.

#2 The Sunk Cost Effect

The more effort we’ve put into something, the harder it is to let go. The sunk cost fallacy keeps people investing time, money, or emotion in what’s familiar — even when a better choice exists.

Older customers and long-time team members have often invested years mastering a process or system — even if it’s simple like renewing their subscription with a long form and brochure or calling their favorite staff member. It can even feel like a ritual. Asking them to switch feels like discarding that hard-won competence.

Acknowledging that emotional investment — rather than fighting it — helps people feel seen and supported through change.

#3 Path & Environment Matter

Even early adopters can get thrown if the environment and design doesn’t support new behavior.

If the Wi-Fi dies, a password doesn’t work, or the process takes longer than expected, frustration will take over.

Poor training, unclear guidance, inaccessible UX, or lack of visible role models all reinforce the status quo.

The fix isn’t another reminder email. It’s a smoother path: better signage, reliable Wi-Fi, clearer language, and visible support. Change sticks when the process feels natural, not forced.

Why Older Adults Are Sometimes More Resistant

Laura Carstensen’s Socioemotional Selectivity Theory (1995) explains that as people age, their motivational priorities shift:

Older adults seek emotionally meaningful experiences — enjoyment, connection, and satisfaction.

Younger adults focus on the future, novelty, and saving time.

That means older audience may value comfort, joy, and emotional payoff in order to adopt tech instead of saving time.

For example, a digital program that helps grandma connect with their grandchildren has emotional ROI, making the change stick.

When the change feels emotionally positive — not just efficient — they’re more likely to stick with it.

How to Encourage Full Adoption

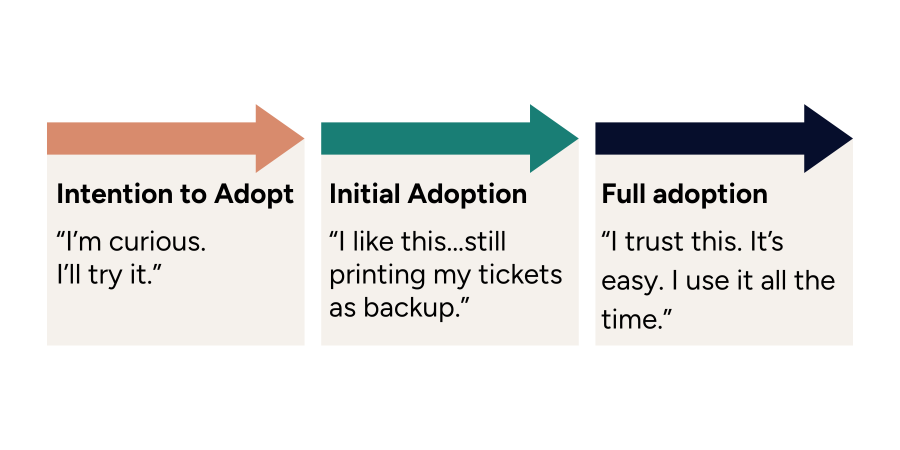

People rarely trust new technology right away. They move through three phases to adoption:

A 2014 study on Internet use among adults 40–70 (Lee, Han, & Chung) expanded the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) — traditionally focused on usefulness and ease — to include emotional and social factors.

Their model adds:

Perceived Enjoyment – Is it satisfying or fun to use?

Subjective Norms – Are people like me using it?

Internet Stress – Does it make me anxious or frustrated?

Socioeconomic Status – Do I have the tools and support to keep up?

Their biggest takeaway: once people, especially ages 40+, decide the enjoyment outweighs usefulness. People continue using technology because it feels good — not because it’s efficient — similar to Carstensen’s Socioemotional Selectivity Theory.

How to Get People to Use Tech & Love It

#1 Social Proof & Norms

When people aren’t sure whether they should take a risk with their money or time, they look to others like them to see what they’re doing.

A UK study tested a few anti-litter signs and found that “9 out of 10 people use a bin” worked best—better than “1 out of 10 people litter” or warnings about £150 fines. People are more likely to copy good behavior when it feels like that’s what everyone else is already doing.

Behaviour Change Cornwall: https://behaviourchangecornwall.co.uk/signs-to-stop-plastic/

That’s why saying things like “80% of subscribers read digital programs the week before the performance” or “4/5 of our audience members use mobile ticketing” will convince others who have not adopted technoglogy to at least try it.

Adding short stories further builds trust.

“One of our longtime subscribers told us she was nervous to use mobile tickets, but now she loves being able to text them to her friends.”

#2 Design Nudges (and Remove Sludge)

How you design your technology or system matters more than messaging ever could.

Nudges make the action you want your audience to take easy:

Pre-fill forms so users don’t need to start from scratch.

Make the mobile option the default, not the add-on.

Offer a small reward, like a free drink pre-order for first-time app users.

Sludge or designing so your audience has to put forth unnecessary effort (think long phone menues and questions that make it take forever to get to a human) slows adoption.

Examples:

When the San Diego Symphony launched Skip the Line and Pre-Order features through Instant Encore’s mobile app, they led with convenience (not the tech). The headline wasn’t “Try our mobile upgrade.” It was “Walk straight in and enjoy your night.”

That framing turned a functional tool into an emotional benefit — less waiting, less stress, more time for what matters.

Many audience members complain about digital programs. Livermore Valley Arts framed their digital program notes as learning about the show way before the show, so you’re not speed reading before the curtain as you would a paper program.

#3 Speak to Your Audience’s Identity

People adopt faster when it aligns with who they believe they are.

“Modern event-goers use mobile ticketing.”

“You already order coffee on your phone — now your tickets are just as easy.”

Position new behavior as consistent with identity, not in conflict with it.

Instant Encore Example: Edmonton Symphony Orchestra appealed to people’s identity of caring about the environment by telling them they’re reducing paper waste.

#4 Segmentation & Rollout Slowly

Not every audience member learns at the same pace. Start with the people most likely to help you — loyal subscribers, donors, or regular attendees. Ask them to test and share feedback.

Then move to the early majority, using real testimonials and practical guidance. For those slower to change, offer hands-on support: a table in the lobby, a friendly face, or clear signage.

When patrons see someone they relate to succeeding, adoption feels safer.

“When our donors started telling each other, ‘I used my phone tickets — it was easy,’ we saw the shift happen faster than any email campaign.”

The Short of It

People resist change when it’s time consuming and frustrating.

When we make it clear, easy, rewarding, and aligned with someone’s identity — tech adoption will follow.

Sources

Arkes, Hal R., and Catherine Blumer. “The Psychology of Sunk Cost.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 35, no. 1 (1985): 124–140.

Carstensen, Laura L. “Evidence for a Life-Span Theory of Socioemotional Selectivity.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 4, no. 5 (1995): 151–156.

Davis, Fred D. “Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology.” MIS Quarterly 13, no. 3 (1989): 319–340.

Heath, Chip, and Dan Heath. Switch: How to Change Things When Change Is Hard. New York: Broadway Books, 2010.

Lee, Euehun, Semi Han, and Yanghon Chung. “Internet Use of Consumers Aged 40 and Over: Factors That Influence Full Adoption.” Social Behavior and Personality 42, no. 9 (2014): 1475–1488.

Poldrack, Russell A. “Can Cognitive Processes Be Inferred from Neuroimaging Data?” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 10, no. 2 (2006): 59–63.

Refill UK. “Don’t Be a Tsser: How to Reduce Littering with Effective Signage.” 2021. https://www.refill.org.uk/dont-be-a-tsser-how-to-reduce-littering-with-effective-signage/.

Thaler, Richard H., and Cass R. Sunstein. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

Wood, Wendy, Jeffrey M. Quinn, and Deborah A. Kashy. “Habits in Everyday Life: Thought, Emotion, and Action.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 83, no. 6 (2002): 1281–1297.